The Tomato’s Journey: Poetry, Pride, and Prosperity…

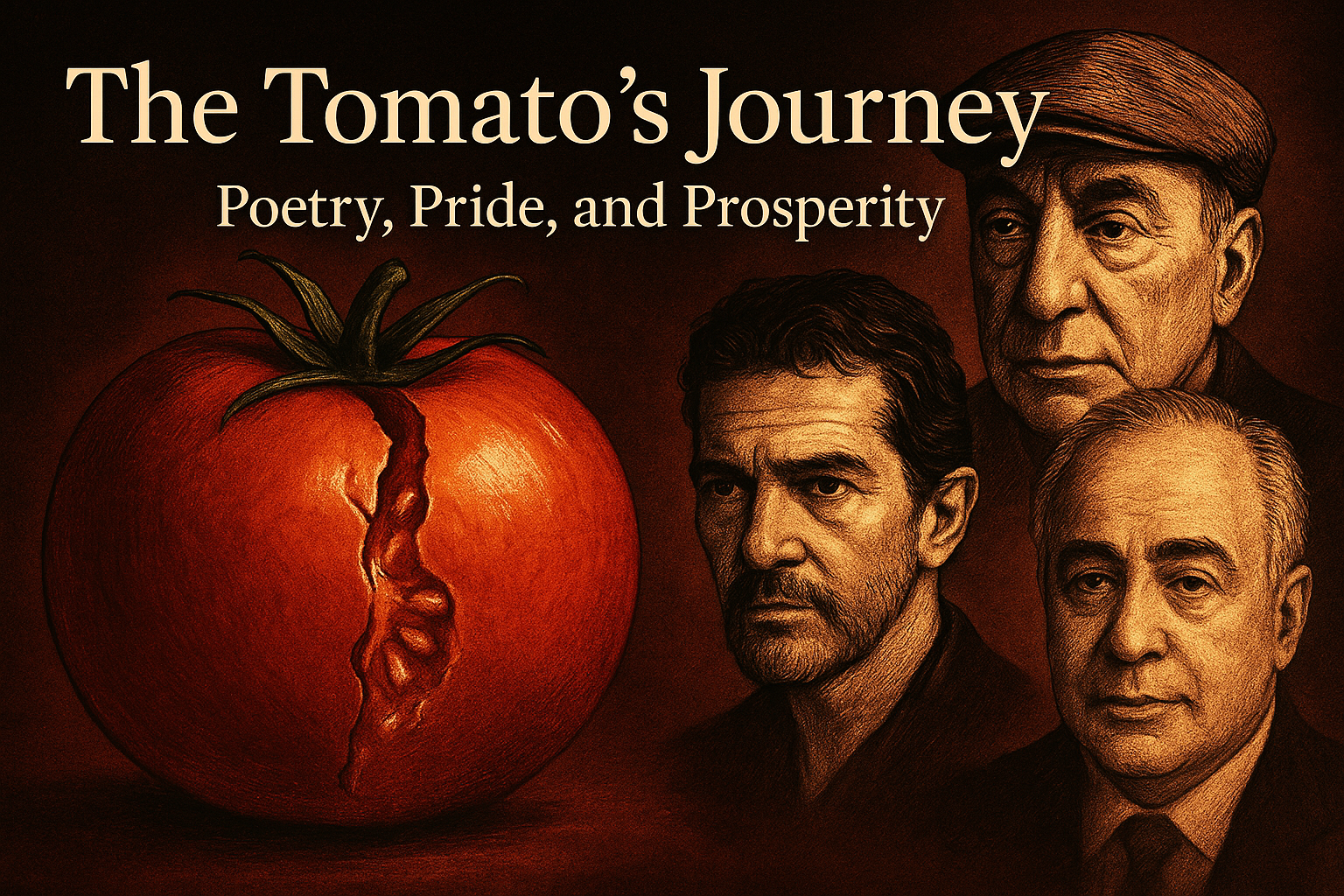

“Pablo Neruda found in it the poetry of abundance. Antonio Banderas upheld it as a symbol of dignity. Don Félix María García turned it into a source of prosperity for his nation. Three men, two continents, three perspectives—but one fruit. A fruit that connects soil to soul, kitchens to empires, and memory to the future…

Just a Single Penny in 2025—Yet the Work Burns Bright

250,000 readers. Countless hours of independent analysis. And in 2025—just a single contribution.

We uncover the patterns where geopolitics meets energy — work powered by rigorous research, licensed data, and a commitment to clarity in an age of noise. But even the brightest flame needs fuel. Always, just a single pound, euro, yen, franc, mark, crown, or rupee is enough. Supporting us isn’t impossible — it’s what keeps the lights burning.

This keeps the imagery (“brightest flame”) but appeals to support a bit smoother and easier to read.

Support our work:

PayPal: gjmtoroghio@germantoroghio.com

IBAN: SE18 3000 0000 0058 0511 2611

Swish: 076 423 90 79

Stripe: [Donation Link]

If you can’t give, share on X, LinkedIn, or Energy Central. It costs nothing and can carry the truth further.

https://x.com/Germantoroghio/status/1957682348461302215

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/tomatos-journey-poetry-pride-prosperity-germ%C3%A1n-toro-ghio-aue5f

The times are uncertain. The need for clarity is not.

All rights are reserved to German & Co.

Germán & Co, Karlstad, Sweden | August 19, 2025________________________________________

Copyright Notice: 2025 Germán Toro Ghio. All rights reserved.

________________________________________

#Agriculture #FoodIndustry #GlobalMarkets #CulturalHeritage #Storytelling

________________________________________

Introduction:

The Tomato’s Unlikely Rise Imagine a world without tomatoes—no spaghetti al pomodoro, no gazpacho andaluz, no ketchup, and no Bloody Mary. Hard to picture. Yet for centuries, this vibrant fruit was met with suspicion and fear in Europe. Brought from the Americas by Spanish conquistadors, tomatoes were initially believed to be poisonous, associated with the deadly nightshade family. It took nearly 200 years for Europeans to embrace the tomato, transforming it from a feared fruit into a cornerstone of global cuisine.

But the tomato’s story isn’t just about culinary redemption. It’s also a story of love—celebrated by poets, farmers, and cultures across the world. Among its most passionate admirers was Pablo Neruda, the Chilean poet, communist, sybarite. Women, borgoñas with dust thick on their bottles—especially the ones he bought with the few coins from his Nobel Prize—all could wait. But not the tomato. For this fruit, he felt a genuine, unashamed passion. So much so that he wrote his Ode to the Tomato (Oda al Tomate), turning it into a symbol of life, love, and revolution. Neruda’s ode reminds us that the tomato is more than food; it is a muse, a metaphor, and a vessel of our shared human experience.

And yet the arc of history bent in its favour. In Naples, among the poor and the hungry, the tomato was redeemed. Combined with pasta, it created a cuisine that would conquer the Mediterranean and beyond. From that moment, the fruit of suspicion became the crown of kitchens. Today, it rules not only on the table but in the field, the factory, and the market: 186 million tons harvested each year, a global trade worth billions, an empire of flavour and industry.

But numbers alone cannot capture its meaning. The tomato carries poetry, pride, and prosperity. In Pablo Neruda’s verses, it became a hymn to abundance; in Antonio Banderas’ wit, a defence of cultural dignity; in Don Félix María García’s vision, the foundation of a Dominican agricultural revolution: three figures, three continents, one destiny.

This is the journey of the tomato — from suspicion to sovereignty, from fruit to force, from the silence of seeds to the red destiny of nations.

________________________________________

I. Suspicion: The Poisoned Crown

The story begins not in Europe but in the sacred gardens of the Americas. Long before conquistadors set sail, the peoples of Mesoamerica cultivated the tomato with reverence. The Nahua called it tomatl, a fruit both nourishing and symbolic, woven into ritual and diet. It was a fruit of the sun—its red skin recalling fire, its seeds recalling fertility.

When Hernán Cortés marched on Tenochtitlán, he carried more than gold back to Spain. He had seeds, small and fragile, that contained within them the future of global cuisine. Yet Europe did not recognize the gift. Instead, it recoiled.

The tomato belongs to the nightshade family, kin to belladonna and mandrake. Physicians and priests alike declared it dangerous. Aristocrats who tasted it fell ill and sometimes died, though not from the tomato itself but from the lead of their pewter plates, whose acidic reaction the fruit had merely awakened. Rumour does not ask for proof. The tomato became the “poison apple,” a fruit of death.

Two centuries passed under this shadow. In the markets of Paris and London, the tomato remained ornamental, grown for beauty rather than consumption. But in Naples—poor, crowded, and hungry—the people took a chance. They discovered that tomatoes cooked with pasta created something miraculous. Out of suspicion was born a national cuisine. What the aristocrats rejected, the poor embraced, and from their embrace came glory: spaghetti al pomodoro, pizza margherita, the Mediterranean table.

Suspicion has given way to sovereignty.

________________________________________

II. Empire: The Red Continent

Today, the tomato commands a world-spanning empire. The production is staggering:

China: more than 68 million tons annually, nearly 37% of the global harvest.

India: over 20 million tons, with greenhouse cultivation expanding at an unprecedented speed.

Turkey and the United States: 13 and 12 million tons, respectively.

Italy and Spain: smaller producers, but global powers in processing and shaping how the fruit is consumed everywhere.

The industry is no longer just fields and farmers; it is processing, packaging, and global logistics. Italy transforms 64% of its harvest into sauces, pastes, and canned goods. Spain follows with 39%, and the United States with 10%. India, despite its vast output, processes barely 1%—a sign of both untapped potential and lost opportunity.

By 2024, global tomato processing reached nearly 46 million tons, with China again leading the charge. Entire economies are now tethered to the fruit: $10.7 billion in international trade, 38% of global output in processed goods, and rising consumption in West Africa and the Middle East, where demand has surged nearly 30%.

Yet this empire is fragile. Climate change threatens harvests: Iran’s 2024 crop collapsed by 35% as temperatures rose beyond 113°F. Meanwhile, controlled-environment agriculture, with its glass houses and artificial light, produces yields six times higher than open fields. The tomato, once feared as unnatural, now thrives most securely in engineered environments.

It is a paradox. A fruit once accused of poison now survives by embracing technology that defies nature.

________________________________________

III. The Poet: Abundance in Red

Pablo Neruda, the Chilean Nobel laureate, understood what others missed. To him, the tomato was not only food but metaphor. In his Ode to Tomatoes, he described summer streets overflowing with crimson, "bright halved like flesh, juice running through the city like liquid sun."

He did not see a mere fruit. He saw a symbol of earth’s generosity, a vessel of life, a connection between soil and soul. Neruda’s tomato was the harvest of centuries, the embodiment of abundance offered freely by the planet. His poetry elevated it from the kitchen to cosmos.

Neruda’s genius was to recognize in the humble tomato the eternal rhythm of human existence: the cycle of seed, fruit, and nourishment. For him, the red orb was proof that poetry resided not in marble statues or royal palaces but in the food that sustained the poor. In celebrating the tomato, he celebrated life itself.

________________________________________

IV. The Actor: Pride in Red

If Neruda turned the tomato into poetry, Antonio Banderas turned it into pride.

On an American talk show in 2019, Jimmy Fallon mocked Spain as “the Mexico of Europe.” The audience laughed. Banderas, dignified yet smiling, replied: “We gave you the tomato. And you gave us... The Tonight Show.”

It was a moment of wit, but beneath the laughter lay centuries of history. Spain had carried the tomato from the Americas to Europe; Europe had taken it to the world. In Banderas’s reply was a quiet reminder: modern cuisine itself owes a debt to Spanish ships and Indigenous fields. The tomato was not trivial—it was heritage.

In that instant, I became more than an actor. He became ambassador. With a single phrase, he defended the nation’s role in shaping global taste, and did so with elegance rather than anger.

The tomato, once despised, had become a symbol of cultural pride.

________________________________________

V. The Builder: Prosperity in Red

But poetry and pride alone cannot feed nations. To do that, the tomato required builders—entrepreneurs willing to transform vision into industry.

In 1966, in Santiago de los Caballeros, the historic heart of the Dominican Republic’s Santiago Province, Don Félix María García gathered with a small group of farmers in the town of Navarrete. The men, weathered by years of tobacco and plantain cultivation, listened in silence as García spoke.

He promised not miracles, but tomatoes—a crop many mistrusted. García insisted, "The tomato is not just for the kitchen; it's for the market, the factory, the future."

The farmers glanced at one another, sceptical. How could this soft, perishable fruit compete with the hard-earned traditions of the valley? How much money could be made from something that spoils in days? One finally muttered the doubt of all: “Eso es para Italia, no para nosotros.”

García did not flinch. He pointed to the soil, rich and dark beneath their feet. He described irrigation systems that could draw life from scarce rivers, greenhouses that could shield delicate crops from storms, and processing plants that could preserve tomatoes long after the harvest. He painted a vision not of a farm, but of an ecosystem—farmers, factories, and markets bound together by a single fruit.

It sounded improbable, almost impossible. And yet in his conviction lay a power stronger than machines or money. “With the tomato,” García said, “we can build something that belongs to all of us. It’s something that will put Navarrete and the Dominican Republic on the map.”

That same year, he founded Grupo Linda, naming it for the beauty (linda) he saw in his homeland’s potential. By February 1967—barely eight months after planting—the first harvest was processed. What had been dismissed as folly revealed itself as the beginning of an agricultural revolution.

The obstacles were formidable. Water was scarce, machinery costly, and credit uncertain. Yet García pressed forward. It provided seeds and training to reluctant farmers, guaranteed purchases for their crops, and invested in technology that met international standards. He understood that prosperity would come not from individual triumphs, but from the strength of communities bound together.

Under his leadership, Azua Province became the Dominican Republic’s “Tomato Capital.” Grupo Linda’s products travelled far beyond Caribbean shores, reaching markets in North America and Europe. The company diversified into corn, beans, pigeon peas, but tomatoes remained its beating heart.

Even now, the annual Industrial Tomato Festival of Azua celebrates this vision, attracting visitors from across the Caribbean. Grupo Linda endures as a family enterprise, guided by García’s descendants, who uphold his creed: agriculture is not merely commerce—it is dignity, community, and destiny.

In García’s hands, the tomato ceased to be a fragile fruit. It became a weapon of national confidence, a scarlet banner of prosperity.

________________________________________

Epilogue: The Red Destiny

The tomato’s journey is not merely agricultural. It is civilizational. In its red flesh we read the drama of humanity itself: discovery and suspicion, rejection and triumph, fragility and empire.

Once dismissed as poison, it now nourishes billions. Once confined to gardens of curiosity, it now spans five million hectares of earth. Once a symbol of mistrust, it has become an emblem of connection.

Pablo Neruda saw in it the poetry of abundance. Antonio Banderas defended it as a matter of dignity. Don Félix María García transformed it into prosperity for his nation. Three men, three continents, three visions—but one fruit. A fruit that links soil to soul, kitchens to empires, memory to future.

Today, as climate change reshapes our fields and technology encases harvests in glass, the tomato remains what it has always been: a test of our imagination. It reminds us that revolutions may begin not with swords or machines, but with seeds. That prosperity can be built not on conquest, but on cultivation. That identity can be carried not in flags, but in flavors.

The tomato is no longer the stranger, the feared intruder. It is the universal sovereign of cuisine, the silent witness of exchange, the scarlet ambassador of human resilience.

And when the histories of this century are written, perhaps the humble tomato will appear not only as food, not only as trade, but as proof—that humanity, in all its divisions and ambitions, is still capable of unity through something as simple, as enduring, as a fruit that once crossed the ocean in silence and changed the world forever.

________________________________________

The Author

Germán Toro Ghio is among the rare commentators able to traverse the frontiers between energy, politics, and culture. With an audience of more than a quarter of a million readers worldwide, he has become a reference point in the global energy debate. As an Expert in The Energy Collective and a contributor to Energy Central’s Power Perspectives™ series, he has distinguished himself by rendering legible the often opaque interplay of markets, geopolitics, and infrastructure. His career in the sector spans more than three decades, including leadership roles such as Corporate Vice-President of Communications for AES Dominicana, where he pioneered strategies for natural gas development and regional energy integration.

Yet Toro Ghio’s path extends far beyond kilowatts and contracts. Before entering the energy sector, he navigated the realms of literature, diplomacy, and cultural policy. He served as Executive Secretary of the Forum of Culture Ministers of Latin America and the Caribbean; he co-authored Colombia en el Planeta with William Ospina and Beatriz Caballero of the La Candelaria Theater Group for the UNDP; he collaborated with the Nicaraguan poet-priest Ernesto Cardenal; and, with the encouragement of Octavio Paz, he revived Carlos Martínez Rivas’s La insurrección solitaria—restoring Central American poetry to its rightful place in the currents of twentieth-century literature.

As a writer, he has published works ranging from Nicaragua Year 5—a documentary testimony in images, catalogued by Lund University—to The Non Man’s Land and Other Tales. He has directed and overseen literary editions such as Joven arte dominicano, promoted by Casa de Teatro in Santo Domingo and distributed to universities across the world.

Chilean filmmaker and political scientist Juan Forch—an architect of Chile’s historic 1990 “NO” campaign, later dramatized in Pablo Larraín’s Oscar-nominated No—has written of Toro Ghio’s narratives that they “enrich our understanding of history beyond traditional battlefields and royal courts,” praising journeys that move effortlessly “from the discomfort of a Moscow hotel to the exhilaration of the Nicaraguan jungle.”

________________________________________

Doubt.

If it concerns the soul, or life itself. If it turns to the sun, or the silence of night. If what is needed is writing or the sharpening of words. Whether the matter is crisis, politics, corporate communications, or energy.

You may call. You may write. At any hour of the day.

Within 24 hours, you will receive an answer. This is not speculation. No delay. But clarity — composed, complete, decisive.

Honorarium: €62.5 for the inquietud Germán Toro Ghio, Strategic Analyst · Writer · 30 Years of Experience...

In December 2023, Energy Central recognized outstanding contributors within the Energy & Sustainability Network during the 'Top Voices' event. The recipients of this honor were highlighted in six articles, showcasing the acknowledgment from the community. The platform facilitates professionals in disseminating their work, engaging with peers, and collaborating with industry influencers. Congratulations are extended to the 2023 Top Voices: David Hunt, Germán Toro Ghio, Schalk Cloete, and Dan Yurman for their exemplary demonstration of expertise. - Matt Chester, Energy Central

You can't possibly deny me...

Have a wonderful day filled with good health, happiness, and love…